Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Claudio Abbado, director

Category: Music Classical

Igor Stravinsky: Funeral song Op.5

Mariinsky Orchestra

Valery Gergiev, director

Mozart: Clarinet Concerto in A major K.622

Clarinet: Robert Marcellus

Conductor: George Szell

Orchestra: Cleveland Orcherstra

Joseph Haydn: The Seasons

Hanne…….Dorothea Röschmann, soprano

Lukas……..Michael Schade, tenor

Simon……..Florian Boesch, baritone

Konzertvereinigung Wiener Staatsopernchor

Ernst Raffelsberger, chorus master

Wiener Philharmoniker

Conductor: Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Philip Glass: String Quartets No. 5, 4, 2, 3

1-5: String Quartet No. 5

6-8: String Quartet No. 4 (starting at 27:50)

9-12: String Quartet No. 2 (starting at 45:03)

13-18: String Quartet No. 3 (starting at 52:50)

The Kronos Quartet:

David Harrington, violin

John Sherba, violin

Hank Dutt, viola

Jennifer Culp, cello

Henryk Gorecki: Symphony No. 3

Dawn Upshaw, soprano

London Sinfonietta

David Zinman, direction

Hector Berlioz: Les nuits d’été

Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra

Véronique Gens, soprano

Lionel Bringuier, director

“Les nuits d’été (Summer Nights), Op. 7, is a song cycle by the French composer Hector Berlioz. It is a setting of six poems by Théophile Gautier. The cycle, completed in 1841, was originally for soloist and piano accompaniment. Berlioz orchestrated one of the songs in 1843, and did the same for the other five in 1856. The cycle was neglected for many years, but during the 20th century it became, and has remained, one of the composer’s most popular works. The full orchestral version is more frequently performed in concert and on record than the piano original. The theme of the work is the progress of love, from youthful innocence to loss and finally renewal.”

Toru Takemitsu: From me flows what you call Time

La jolla symphony

Steven Schick, director

John Tavener: Total Eclipse

Saxophone – John Harle

Countertenor Vocals – Christopher Robson

Soprano Vocals – Patricia Rozario

Tenor Vocals – James Gilchrist

The Academy Of Ancient Music

The Choir of New College, Oxford

Paul Goodwin, director

Tempi…

Francis Poulenc: Stabat Mater

Choir of Clare College, Cambridge

Chor of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra

Christopher Robinson, director

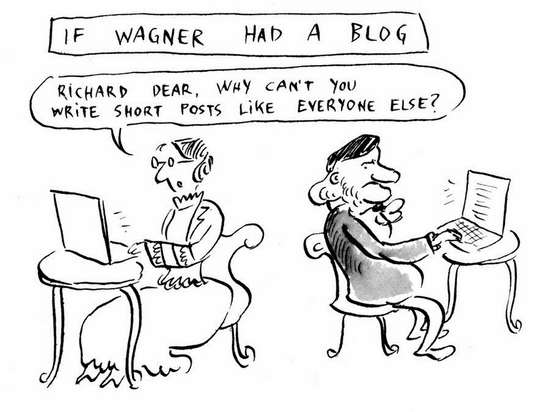

Wagner

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Concerto for Birds and Orchestra “Cantus Arcticus”, Op. 61

-

- The Bog

- Melancholy

- Swans MigratingRotterdam Philharmonic

Robin Ticciati, director

Comments by Chris Morrison, Allmusic.com:

“…In 1972, Einojuhani Rautavaara was commissioned by the University of Oulu, Finland, to write a piece for its first doctoral degree ceremony. Tradition would have him create a ceremonial festive cantata, but Rautavaara responded instead with the unusual Cantus Arcticus, often referred to as a Concerto for Birds and Orchestra, in which taped bird songs (some recorded in the vicinity of Oulu, others around the Arctic Circle and the marshlands of Liminka) interact with the orchestra.

The work is in three movements, each of which features a different set of bird songs. The first movement, titled “Suo” (“The Marsh”), opens with an impressionistic melody for two solo flutes, later joined by other woodwinds and by a recording of bog birds in springtime. A slow, rich, melody in the strings is superimposed over the winds and bird songs as the mood mellows, and the movement dies out with a reminiscence of the opening flute melody. The song of the shore lark, lowered by two octaves to turn it into what Rautavaara has called a “ghost bird,” opens the second movement, “Melankolia” (“Melancholy”). A quiet melody in the strings enters tentatively and spins itself out, gaining in intensity as it goes. The movement ends as it began, with the shore lark. The final movement, “Joutsenet muuttavat” (“Swans Migrating”), opens with the chaotic sound of a large group of swans, combined with string tremolos and bird imitations in the woodwinds. This complex texture was described by Rautavaara thus:: “I imagined they [the swans] fly straight to the burning sun.” As in the first movement, a slow, chorale-like melody in the strings emerges. The swan sounds increase in volume, and after a climactic cymbal crash and brass calls, the music and the swans’ songs fade into the distance amid the gentle sounds of harp and percussion…”

Debussy: String Quartet in G minor (1892)

Emerson String Quartet

Comments by Michael Jameson:

“Debussy began work on the composition of his only string quartet in 1892. Little documentary evidence, save for one or two passing oblique references in letters to friends remains to indicate his rate of progress. The final movement, however, caused him no little trouble, and only in August 1893 did Debussy feel able to write to his colleague André Poniatowski that “I think I can finally show you the last movement of the quartet, which has made me really miserable!”

Cast in the traditional four movements, Debussy’s Quartet in G minor, Op. 10 has as its most distinctive feature its overarching preoccupation with timbre and sonority. The work as a whole offers a compendium of string-playing techniques, yet it also displays a concision of thought rare, perhaps, in a composition often regarded (along with the quartet by Ravel) as one of the seminal impressionist works in the string quartet genre.

Its fascinating and readily palpable thematic concentration seems all the more remarkable when one realizes that the very first theme of the opening movement (Animé et très décidé) comes to furnish almost all of the diverse thematic components for the entire work. Another ingenious feature (possibly less immediately apparent to the listener at first hearing) is that the quartet is less dominated by melodic or harmonic considerations than by a rhythmic flexibility which carries the potential for seemingly endless variety. In this respect, Debussy’s string quartet seems to strongly prefigure those by Bartók. Yet it remains unmistakably a work dominated by the sensuality and longueurs of French late nineteenth century Romanticism, a strong feature of the slow third movement (Andantino doucement expressif).

The work is also strongly predictive of the disjunctive and highly polarized new musical language that would assert itself in the two decades following its completion. The Scherzo (Assez vif et bien rythmé), for example, makes use of the disruptive sonic confrontations that can occur when rapidly alternating pizzicato and bowed passages produce what one commentator has described as “a confusion that forces the listener to concentrate on the textures, rather than the linear form of the music.” These apparently disparate elements are then welded together in a finale of striking economy of means, and only at the close does it become really clear that the opening gestures of the work have actually altered themselves and coalesced to produce an organic unity of some 25 minutes’ duration.

The work was to be dedicated to Ernest Chausson, whose personal reservations eventually diverted the composer’s original intentions. Debussy sold his score for a mere 250 francs to the publishers Durand & Cie, who, as he later recalled, “were cynical enough about it to freely admit that what they were paying me didn’t cover all the labor this ‘work’ has entailed.” Not surprisingly, the quartet was widely misunderstood at its premiere, given by the Ysayë Quartet on December 29, 1893. At the time, the composer Guy Ropartz was the lone voice in a wilderness of critical lack of interest; he described the quartet as a work “dominated by the influence of young Russia (interestingly, Debussy’s patroness in the early 1880s had been Nadezhda von Meck, better known for her support of Tchaikovsky); there are poetic themes, rare sonorities, the first two movements being particularly remarkable.”

Olivier Messiaen: Turangalîla-Symphonie

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France

Direction: Myung-Whun Chung